Fair Street, Butler alums celebrate their beloved alma maters

Fair Street, Butler alums celebrate their beloved alma maters

A photo of the first Fair Street High School football team in 1950.

For The Times

2 of 14View Larger

PreviousPause Media SlideshowNext

PreviousView SlidesNext

By Jessica Jordan

jjordan@gainesvilletimes.com

POSTED Sept. 5, 2009 11:44 p.m.

13 Images 1 Video

1 video in Multimedia.

Forty years ago, this fall, the halls of Butler High School were strangely silent.

No lockers slammed shut at the ring of the bell. No gossip was whispered in the cafeteria.

It was 1969, and Hall County’s all-black school had been closed due to court-ordered integration, which came long after the 1954 Supreme Court ruling that deemed segregated schools as inherently unequal.

That fall, hundreds of local black students suddenly found themselves behind desks at Gainesville High School, a place is once forbidden to them.

The building on Athens Street that had educated a generation and molded their character was history. But for nearly the past 20 years, the Fair Street-Butler Alumni Association resurrected the memories of the county’s black schools with a biennial reunion on Labor Day weekend.

Gainesville resident Martha Mays graduated from Butler Highs’ last class. She serves as president of the association that orchestrated this year’s three-day reunion, which wraps up with today’s luncheon at the Georgia Mountains Center.

Mays said the closing of Butler High was bittersweet.

“We had really hoped that because Butler had a lot of new age things, like air conditioning and a French lab, they would come to our school,” she said, referring to the city’s white students. “But they didn’t. And, of course, we were saddened by the fact that our school was closed. But with integration, there was supposed to be opportunity and progress.”

Mays said the reunion is when alumni from Fair Street School, once a school for black students in kindergarten through grade 12, and Butler High come together in Gainesville and exchange tales from days.

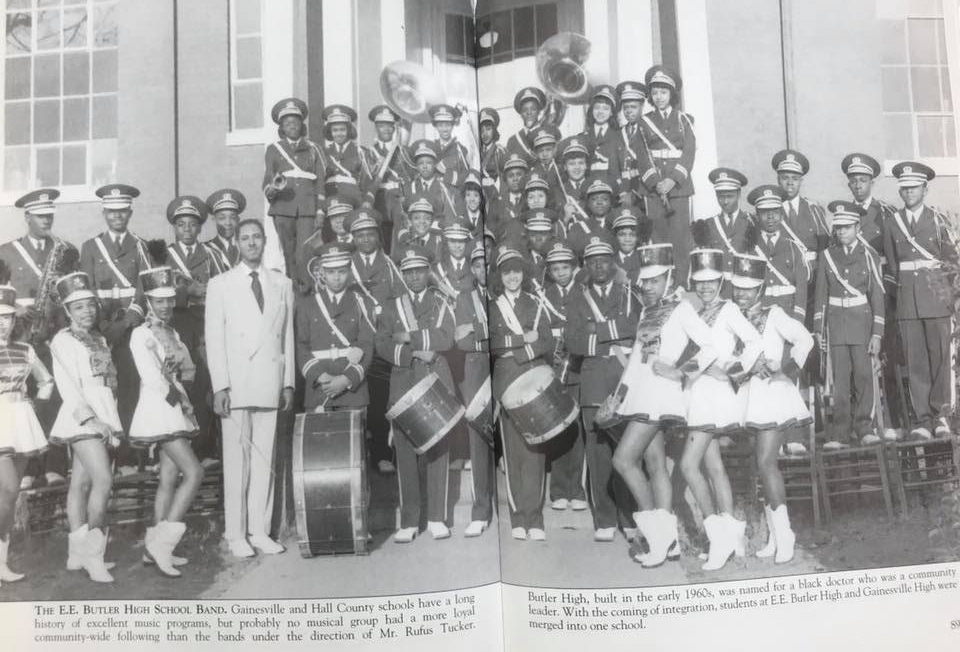

Stories of secret crushes, memories of spending lunch money at the sweets shop, and of marching bands crashing through the Gainesville square booming the anthem “Our Boys are Gonna Shine Tonight” resurfaces at the reunion.

Sometimes, the conversation drifts to the mystery of the whereabouts of Larry Marlow, Butler Highs’ lone white student who dared to cross the line into Gainesville’s southside school. And there are memories of long walks to school up red dirt roads and the stale recollections of denied opportunity.

Mays, who has never missed a reunion, said she feels it is important for the black school’s alumni to bring their children and grandchildren to the event.

“It is a part of history. You don’t know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been,” she said. “… This is a way for them not just to hear you talk about it, but see it.”

Mays said she wants younger generations to understand how it was then.

“The saying it takes a village to raise a child we were like that. You knew you always had to be respectful and be on Q because somebody was always watching,” she said. “We believe in each one, teach one and we try to pass it on.”

And it’s just plain fun.

“I guess we really enjoy each other, and each year, people come who have never been before,” Mays said. “So many of us move away. Very few stay here. And they come back, and it’s so exciting. You have an opportunity to reconnect with people.”

“We want those people to come back so we can show them how things have changed,” Fair Street-Butler Alumni Association Treasurer Berlinda Lipscomb said.

When she moved back to Gainesville from Ohio, Mary Acree, 69, started the reunion. Acree graduated from Fair Street in 1959 and recalls the warm community she grew up in.

“The whole time I was in Ohio, I was thinking about Fair Street and my friends there,” she said. “I just never forgot. It was a wonderful time in my life.”

As a trumpet player in the Fair Street Band, Acree said she loved it when the band marched through town playing a song “the white folks” loved: “The Beer Barrel Polka.”

Acree said she really got down at the sock hops held in the Fair Street gym. The Friday night prom and Saturday night sock hop remain staples of the reunion.

“Oh, Lord, I used to dance,” Acree said. “I was a boogieing woman back then.”

The music of Jackie Wilson and other soul favorites like Fred Parris and the Five Satins once blared from the Fair Street auditorium.

“In the Still of the Night, that was a slow song,” Acree remembers.

As a band member, Acree also traveled the state with the Fair Street football team, which won state championship games in 1956 and 57. The team remains the only public school in Hall County to win back-to-back state titles.

Celebration of the Fair Street Tigers of 56-57 is this year’s reunion theme. The team and its surviving members were honored at this year’s season-opening Gainesville High football game. The Red Elephant Marching Band even learned the Tiger’s favorite, “Our Boys are Gonna Shine Tonight,” and played the tune as the champions took the field.

Gene Carrithers, 68, was the Tiger’s halfback during those two title seasons. He said the game was the first time he stepped onto the field at City Park more than a week ago since he sported a football helmet in high school.

“It took a long time, but that’s something real special,” he said of the ceremony. “Them recognizing us last Friday night, that got that cake. That was really special. That will stay with us. It took a long time, but it got here.”

Carrithers still cracks a great big smile when he tells the story of the Tigers shutout of Cedartown, their arch rival. Under the leadership of football coach E.L. Cabbell, the young men of Fair Street discovered that champions can come from humble beginnings.

“All of us came up in the projects out there,” Carrithers said. “All of us played that sandlot football, so we were pretty much together when we got in high school. And everything just fell in place.”

The former halfback said his football days ended with high school because there were no college scholarships for black athletes at the time. He said he’s glad things have changed but cant help but wonder what might have been.

“You can make it anywhere now,” he said. “The doors are open.”